Introduction

§1 In 1993, Peter Robinson and Elizabeth Solopova published The Canterbury Tales Project’s (CTP) first complete transcription guidelines that they developed and co-wrote in preparation for their digital edition of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue (Robinson 1996). This article was not merely a description of transcription practices, but a declaration of the principles and aims of the project and a rationale of how the project’s practices were informed by those principles. Since then, Robinson and project director Barbara Bordalejo have revisited these guidelines throughout the ongoing practice of transcription. Some important transcription decisions have been documented in the project’s wiki (Bordalejo and Robinson 2018) and the editorial material of related projects that directors have had a hand in, such as Bordalejo’s contributions to Prue Shaw’s edition of Dante’s Commedia (Shaw 2010). However, there remains a need to formally revisit and review how the practice of transcription has changed and assess how well those practices continue to align with the principles and aims of the CTP, a task which project leaders Peter Robinson and Barbara Bordalejo intend to complete in a future article.

§2 We the authors have over a decade’s combined experience with the CTP at various levels of involvement. Kyle Dase has been working on the project since the outset of Phase 2 in 2014 and has had multiple roles in the project, including most recently acting as one of two project managers overseeing the work of the transcription team. Kendall Bitner has transcribed more pages on the project than any other individual since his first involvement with the CTP in 2016. Both authors have received formal training in manuscript studies and each has gone on to incorporate that training into their research. Dase’s master’s thesis entailed creating a digital edition of the Old English poem, The Wanderer, using the Textual Communities platform and his current dissertation work features a chapter grounded in the study of early modern manuscripts. Bitner’s interdisciplinary master’s program focused on language study and the editing of manuscripts and it culminated in the production of a new edition of Ælfric’s Grammar. Given our combined experience, we have been considered by the project’s leaders something like ideal transcribers and project members.

§3 It is from this viewpoint that we offer the present analysis of the project’s guidelines and their implications. We joined the project as it was implementing and refining its revised guidelines during phase 2, taking part in important ongoing discussions that not only addressed practical matters but had implications for the project’s core principles and aims. We then applied those decisions in practice in our roles as transcribers and supervisor. Ours is a unique perspective as (relative) newcomers to the project involved in the project’s decision-making process at multiple levels and the practice it informs as hands-on users of the guidelines.

§4 In this paper we seek to outline the shifts in transcription practice on the CTP and how these practices are informed by the project’s own principles and aims. Our goal, however, is not merely a description of the end result; we hope that by describing the process by which the project arrived at these new practices, the questions it has had to answer likewise allow for the analysis of how they further clarify and challenge earlier assumptions about those principles and aims. This article is not an updated version of the project’s guidelines, but a genealogy and inquiry into their ongoing development from our point of view as hands-on users and experienced team members, considering how they have changed in light of problems that have arisen on the project, compromises for the sake of efficiency, and technological change. The need for an updated set of guidelines and rationale has become apparent through the development of the present article, however, as there has been an absence of publications on the matter following Robinson and Solopova’s 1993 article despite significant change throughout the transcription process. As stated above, the project leaders, Bordalejo and Robinson, intend to reinvestigate the full transcription guidelines and their rationale in a forthcoming publication. The need for such an investigation, moreover, has only been highlighted through the process of developing the present article.

§5 This article begins by revisiting Robinson and Solopova’s principles of transcription as an interpretative act of translation from one semiotic system to another, exploring how this assertion results in the CTP’s representations of overlapping hierarchies of the text and document. We then provide a short account of other full text transcription projects such as The Piers Plowman Electronic Archive (PPEA), Murray McGillivray’s The Cotton Nero A.x Project, The Commedia Project, and The International Greek New Testament Project (IGNTP), with a special interest in projects that have informed the CTP team’s own practice. Throughout this article, we frequently contextualize the work and aims of the CTP in relation to such similar projects to better demonstrate how the project’s transcription guidelines and practices align with its foundational principles. The project’s own transcription practices based on the principle of transcription as an act of translation are informed by its focus on Chaucer’s work as English literature and, in some instances, an emphasis on the text of the Canterbury Tales rather than on the documents as artifacts. Moreover, we further explore the foundational assertion that the aim of the project is not to produce a definitive transcription, but an open access, collatable, digital transcription, the value of which ought to be judged on its usefulness to other editors and scholars.

§6 Next, we look at how transcription practices have changed over time, focusing especially on the major developments of the use of the apparatus element and how the project treats abbreviation and expansion. These improvements allow for greater specificity in transcription and clarify interpretive decisions with greater transparency. While these changes provide benefits of clarity, certain adaptations of the transcription guidelines have been made as a practical compromise in light of the herculean task of transcribing such a large corpus. For example, regularizing our treatment of certain abbreviations (e.g. final “e”) rather than developing distinct guidelines for specific manuscripts has helped the project to progress in a more consistent and timely way.

§7 Finally, we examine the limitations of guidelines and the need for informed transcribers and flexibility in transcription practice. A set of guidelines that exhaustively anticipates all possible cases is impossible given the complexity and inconsistency of scribal practice. Instead, the project’s guidelines encapsulate the principles and aims of its interpretation and the standing expectation is that an informed transcriber, in coordination with the rest of the transcription team, will implement adaptive transcriptions in unique circumstances. Reviewing the original transcription guidelines reveals that, while the project has adapted its transcription practice in the last twenty-eight years, each of those changes has been in an attempt to better accomplish the overall task of producing a collatable digital transcription of the Canterbury Tales in a timely manner and in alignment with Robinson and Solopova’s original aims—a task that the project team is closer to accomplishing than ever.

Transcription as translation and the advantages of digital transcription

§8 Any project that has carried on for as long as the CTP is bound to experience change. Accordingly, its transcription guidelines and practices have changed considerably over the last twenty-eight years. The project’s core principles, however, grounded in Robinson and Solopova’s discourse on semiotics in “Guidelines for Transcription of the Manuscripts of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue” have remained much the same.

§9 Robinson and Solopova describe the act of transcription not as the mere keeping of a record, but an interpretive act of “translation from one semiotic system (that of the primary source) to another semiotic system (that of the computer)” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 3). When scholars produce a digital edition from medieval manuscript witnesses, they are moving between materially distinct systems of representation:

Any primary textual source then has its own semiotic system within it. As an embodiment of an aspect of a living natural language, it has its own complexities and ambiguities. The computer system with which one seeks to represent this text constitutes a different semiotic system, of electronic signs and distinct logical structure. The two semiotic systems are materially distinct, in that text written by hand is not the same as the text on the computer screen. (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 21)

This remains a fundamental distinction for the CTP’s transcription practice. If one believes that transcription is a matter of objectively recording “what’s on the page,” one ignores the fundamentally interpretive nature of transcription and fails to recognize that an absolutely objective transcription is an impossibility. But once one acknowledges transcription as an act of interpretation (i.e. translation), one’s priorities are directed towards finding the optimal way of representing the semantic meaning present in the manuscript within the new semiotic system of the computer and maintaining transparency for that interpretive act of representation. Of course, what counts as an optimal representation depends largely on the project’s aim. From the outset of the project, the decision was made that “our transcripts are best judged on how useful they will be for others, rather than as an attempt to achieve a definitive transcription of these manuscripts” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 20). Moreover, because interested parties will always have slightly different values and priorities in a transcription, the project’s transcription “[l]ike all acts of translation… must be seen as fundamentally incomplete and fundamentally interpretative” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 21). It still may come as a surprise to those who hear about the CTP that its aim is not a definitive transcription but instead to be as transparent as possible in providing a transcription and to make the team’s work accessible so that others can build upon it to form new transcriptions that better serve readers who have different priorities. This is one of the great advantages of digital transcription. As David C. Parker explains in his discussion on transcription of the New Testament, “[o]nce a transcription has been made, it can be made available as open source, for new editors to use as they choose. They can check it and add features to it without having to do it all again” (2008, 101). Just as Parker has achieved in partnership with different New Testament editors and projects, the aim of the CTP is that its transcriptions will help other scholars to “be able to spend more time studying the data and less time doing the preliminary work” (Parker 2008, 102).

§10 Nevertheless, the project possesses its own biases and priorities when it comes to transcription. For instance, a focus on the text of the Canterbury Tales and the team’s disciplinary framework as part of an English department prioritizes Chaucer’s text over the document as an artifact, where “text” refers to the totality of intentional, meaningful marks present on its physical support, the “document” (Bordalejo 2013, 67). Moreover, ever since members of the CTP first collaborated with evolutionary biologists in 1998 to produce “The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales”, one of its purposes has been to produce a collatable digital transcription compatible with phylogenetic software and techniques (Barbrook et al. 1998). As we discuss below, such prioritization results in a transcription that pays greater attention to the minutiae of textual signifiers while forgoing some aesthetic and artistic features of the manuscripts entirely (e.g. illustrations) while only generally describing others (e.g. illuminations). Just as an interest in the text of the Canterbury Tales compels the team to examine and transcribe every significant witness containing the Tales, it also determines which content in those manuscripts the team records. If, however, editors with an interest in a particular manuscript should come along in the future, they could quite easily adapt the existing transcription to their own principles and choose to prioritize different features of the manuscript (e.g. glosses, marginalia, illustrations) while benefiting from what is already supplied. The CTP’s transcriptions are by no means a definitive iteration of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, but technological developments allow for freely accessible transcriptions in a way that is useful to others and brings future editors significantly closer to developing their own transcription, using the project’s transcriptions as their base.

An account of other full text transcription projects

§11 There are projects in medieval studies that involve similar work but have very different circumstances and goals than those of the CTP. For instance, the CTP differs greatly in scope and precision from The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Given that Cotton Nero A.x. is the only extant witness for the 14th-century poems it contains (i.e. Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight), the transcription team does not concern itself with producing a collatable transcription because there is nothing to collate their text against (Cotton Nero A.x. Project 2010). Instead they examine this manuscript in great detail and even encode distinct letter forms—the CTP does not—and provide examples for each different abbreviation of nomina sacra that occurs in the manuscript (Olsen and McGillivray 2011; see 48–49).

§12 Likewise, The Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, which aims to transcribe the witnesses of Piers Plowman in some fifty manuscripts, is somewhat smaller in scope than that of the CTP—the B-text of the poem is approximately 7,200 lines compared to The Canterbury Tales’ 17,000. Moreover, the PPEA’s self-identification as an archive and its “long-term goal[…] of a complete archive of the medieval and early modern textual tradition of Langland’s poem” belies a completionist attitude of objectivism not present in the CTP (PPEA 2019, “Home”). The PPEA’s interest in producing critical editions of version archetypes of the poem along with documentary editions of each manuscript witness is not entirely different from the CTP’s own editions of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue on CD-ROM (1996) or The Hengwrt Chaucer Digital Facsimile (2000). Their principles, however, beget differences in practice that are not insignificant. For instance, while the PPEA’s editions clearly indicate where editors have expanded abbreviations, its transcriptions rarely record the original abbreviation. As an example, PPEA transcriptional protocols record the example of “ ” (i.e. propter) as, “p<expan>ro</expan>p<expan>ter</expan>,” retaining nothing of the original scribe’s marks of abbreviation (PPEA 2019, “Transcriptional Protocols”). The CTP’s transcriptions, which promotes both transparency and accessibility, encode abbreviation markers in the <am> element and the interpretation of their corresponding expansions in the <ex> element. A CTP transcriber’s treatment of the same example would render as:

” (i.e. propter) as, “p<expan>ro</expan>p<expan>ter</expan>,” retaining nothing of the original scribe’s marks of abbreviation (PPEA 2019, “Transcriptional Protocols”). The CTP’s transcriptions, which promotes both transparency and accessibility, encode abbreviation markers in the <am> element and the interpretation of their corresponding expansions in the <ex> element. A CTP transcriber’s treatment of the same example would render as:

<am>

</am><ex>pro</ex>pt<am>̉</am><ex>er</ex>,

This example allows a reader to see how the transcriber arrived at that particular interpretation of the text.

§13 The CTP has also developed many facets of its transcription practice from the innovations of other full text transcription projects. The team’s use of the apparatus (<app>) element is explicitly modelled on, and extends from, the system used by The International Greek New Testament Project (IGNTP 2016) and its collaborators (see 23–29). The CTP also uses a similar form of the <app> element as in Prue Shaw’s edition of Dante’s Commedia and draws inspiration from the same for many of its decisions regarding abbreviations (see 22–24).

Encoding physical features in addition to our own hierarchical structures

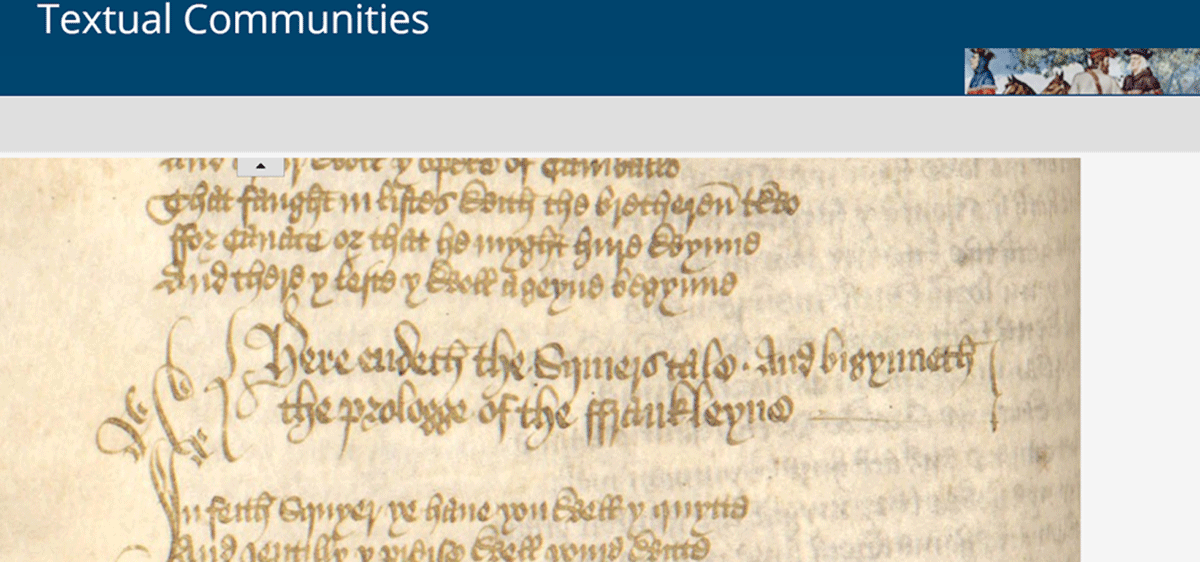

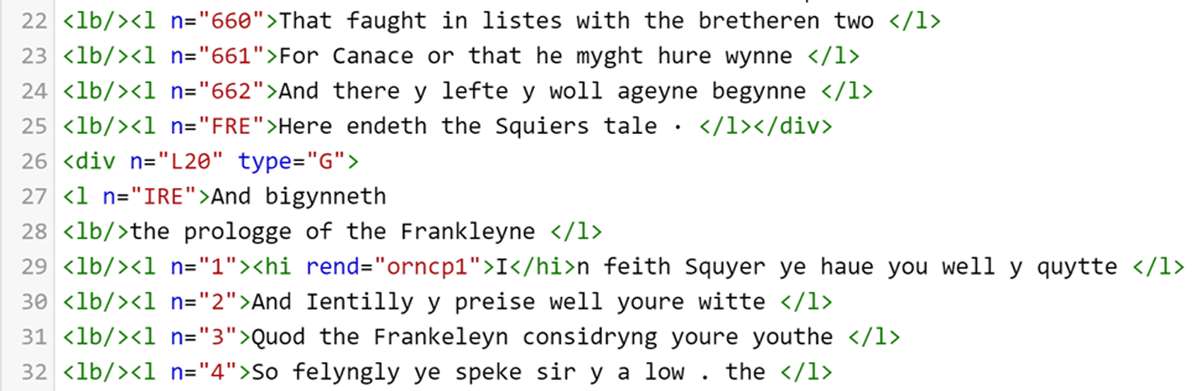

§14 As the CTP’s transcribers translate from one semiotic system to another through the process of transcription they sometimes doubly record divisions present in the primary source witness. This is the result of needing to encode divisions between sections (e.g. tales and links) in machine-readable language while still recording the textual signifiers (e.g. rubrics) meant to convey those same divisions to human readers. (For a distinct yet related discussion of the distinct yet related problem of recording the overlapping hierarchies of the document and of the act of communication and how that was managed in the Textual Communities system, see Robinson 2021.) Because the CTP encodes divisions in a machine-readable hierarchy and also records the text of the document, it sometimes happens that the system captures a single division in two different ways. For instance, the CTP encodes boundaries between sections of the text through the use of the <div> tag but also retains the rubrics that serve the same purpose for medieval readers. Figure 1 shows the rubric, “Here endeth the Squiers tale · And bigynneth the prologge of the Frankleyne,” which signals to a reader a separation between the end of “The Squire’s Tale” and the beginning of “The Franklin’s Prologue”. However, even if this rubric were not present, one still needs a machine-readable way to encode the division. As a result, the CTP team encodes this transition as the end of one division (</div>) and the beginning of another in XML (in this case, <div n=”L20”>, to denote the beginning of Link 20). However, it is important that our transcription record the scribe’s practice here in the document not only because it informed the medieval reader of distinct sections of the text but because such rubrics can help indicate the relationships between textual witnesses. To this end, the CTP team also encodes portions of the single rubric as an explicit at the end of “The Squire’s Tale” and as an incipit at the beginning of “The Franklin’s Prologue”, as shown in Figure 2.

A Rubric separating “The Squire’s Tale” and “The Franklin’s Tale”. Cn, 136v; Austin, University of Texas.

§15 This constitutes encoding the same information—that one section ends and another begins—in two distinct ways: at the level of the text and the level of the document. The one explicitly captures this division as machine-readable while the other is a human-readable representation of the division in the primary source document.

§16 Textual Communities resolves the encoding in so-called “diplomatic” and “edited” views of its digital transcriptions, but its use of these terms requires some explanation. It does not employ a “diplomatic” view in the strict sense Elena Pierazzo describes, where a transcription is diplomatic which:

reproduces as many characteristics of the transcribed document (the diploma) as allowed by the characters used in modern print. It includes features like line breaks, page breaks, abbreviations and differentiated letter shapes. (2011, 463–4)

Our understanding, based on our experience of the project, is that the CTP uses the term “diplomatic” only in a more limited sense. Although its transcriptions include line breaks, page breaks, and abbreviations, its aim is not to reproduce the characteristics of the document as nearly as its digital medium allows. Instead, the CTP’s approach might best be described as a graphemic transcription with graphetic elements. In practice, a certain degree of regularization takes place at the level of transcription so that, for instance, the CTP does not differentiate between distinct letter forms (e.g. long or short “s”) with the exception of capitalization, as discussed below. Similarly, its transcription team uses only a limited set of abbreviation marks rather than all characters potentially available for the sake of an economy of effort in handling the inconsistency of scribal practice. The CTP’s use of “diplomatic” is perhaps best understood, therefore, merely in contrast with “edited” in the context of the viewer in the Textual Communities platform; the principal difference is that in the latter’s “diplomatic” view the CTP transcriptions’ abbreviations are represented by abbreviation marks, while in the “edited” view those marks are replaced by their expansions shown in italics.

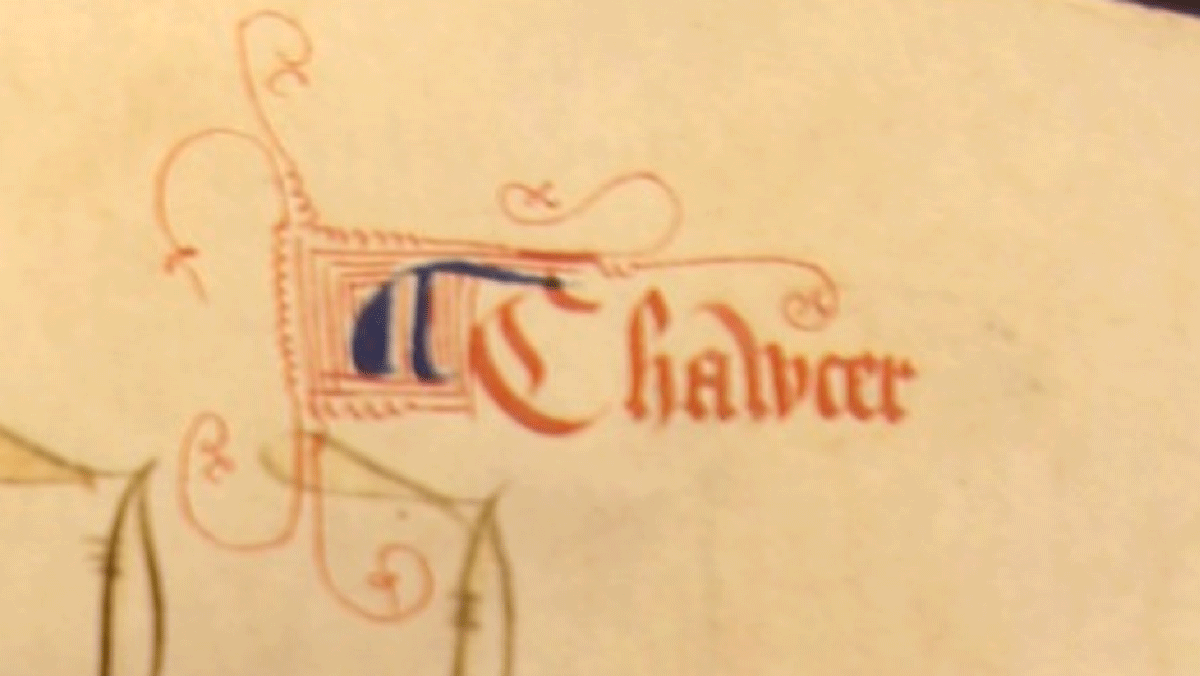

§17 The CTP also encodes certain features of the document such as various marginal texts and ornate capitals and employs distinct elements and attributes for these different types in order to record these features and encode their perceived functions on the manuscript page. A common example is the running header. A running header indicates (usually in the upper margin) what part of the Tales a page contains. Consider the header found in folio 172v of Bo2 (Figure 3). In this instance, “¶ Chawcer” signals that the text below belongs to Chaucer-the-character’s “The Tale of Sir Thopas”, encoded as: <fw type=”header” place=”tm”>¶ Chawcer </fw>. The type “header” indicates that the contained text functions as the page’s header and “tm” signifies its location at the top middle of the page.

Running header in Bo2, 172v; Oxford, Bodleian Library.

§18 In addition to headers, the CTP transcription team encodes footers, catchwords, manuscript signatures, and page numbers, each under the same element <fw> with a unique type. Marginalia that do not fit these types are recorded in a <note> element with an indication of its location. The paraph symbol ¶ (Parkes, 305), moreover, is incorporated into the text it immediately precedes, whether that be a header (as above), a line, or a marginal note.

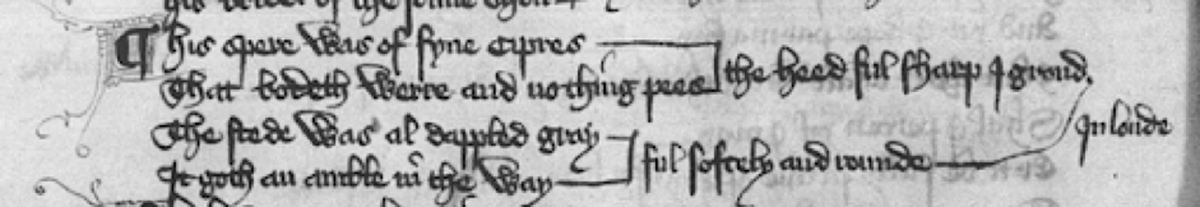

§19 Issues involving the mise-en-page also arise when editing “The Tale of Sir Thopas” where an encoded version of its tail rhymes can hardly reflect the cues expressed in the document. In many manuscripts, this tale is written with offset tail rhymes linked together by brackets as seen in Figure 4. In such cases, the brackets act as a visual cue to inform the order in which one reads the text. However, as stated above, the CTP team’s intention is not to reproduce the visual effect of the document but rather to encode an interpretation of it and to translate its hierarchical structure into a digital system. Accordingly, the transcription team encodes these passages as if they were written in consecutive order from top to bottom. In this instance, therefore, the line beginning with “His spere” is recorded first, that beginning with “The heed” is third, while “In londe” is seventh. Clearly, something of this complex visual structure is necessarily lost when translated into this digital medium, but what is lost is incidental to the CTP’s primary aim of collation.

Tail rhymes in The Tale of Sir Thopas. Ad3, 190v, 169–75; London, British Library.

Transcription as an ongoing process

§20 Many of the CTP team’s transcription practices have changed since the original guidelines were documented in the early stages of the project. Some of these have come about through an organic process of refinement resulting from an accumulation of experience and, especially, from being forced to find solutions for an abundance of unforeseen challenges. Others, however, are directly related to changes in the project’s technological capabilities. Still others have been changed for more pragmatic reasons in the name of an economy of effort. The following discussion will address a number of these changes and offer a rationale for employing them.

§21 One particularly significant change to the CTP’s transcription practice involves the development of its use of the TEI <app> (apparatus) element, which will require some background to illustrate. First, there is the problem that the <app> element is used to solve, namely, how to encode scribal alterations. Here the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) guidelines offer a number of options. The TEI Guidelines principally suggest using a combination of the elements <choice>, <add>, and <del> (TEI P5 2020, 3.4; TEI P3 1999, 18.1). The <choice> element signals that the text contained within it can have multiple interpretations which may be due to the presence of, for instance, abbreviations or scribal alterations, or it can be used to introduce editorial emendations. The <add> and <del> elements signify that the transcriber understands the contained text to be either added or deleted. Scribal markers such as interlinear, marginal, or overwriting text often signal additions, just as underdotted, struckthrough, or scraped text commonly mark deletion. All of these elements (<choice>, <add>, and <del>), however, were problematic for the purposes of the CTP. On the one hand, both the <app> tag and the combined use of <am> with <ex> (both discussed below) tends to render <choice> redundant since they already imply that there is a choice of readings. On the other hand, using <add> and <del> conflates the marks on the document with the transcriber’s interpretation of those marks, which is precisely the point of distinction that the CTP’s use of the <app> element allows one to make (Bordalejo 2013).

§22 The historical development of the CTP’s use of the TEI <app> element can be traced across several earlier projects, here summarized from Barbara Bordalejo’s account in “The Commedia Project Encoding System” (2010). The Società Dantesca’s Dante Online website presented an earlier method of solving the same problem and its guidelines proved “useful as a basis for… transcription protocols” (Bordalejo 2010, 2). There, scribal alterations were encoded within a single element as in, e.g. <di +i0 del>, where “di” is the original reading and “del” is the scribal correction. Further, the “+” symbol indicates an addition that is “i” for interlinear, which is made in the hand of the main scribe, “0”. This system, however, fails to report certain details regarding how scribal corrections are indicated in the document such as whether or how deletion is marked and whether the correction is written out in its entirety or are only partially. Perhaps more importantly, it was not encoded in a way which permits collation of the distinct readings.

§23 A second source in the app tag’s development is to be found in a pair of contemporary Greek New Testament projects (The International Greek New Testament Project and the Codex Sinaiticus Project). These projects used an encoding that more closely resembles the CTP’s own as it forgoes the <add> and <del> elements in these circumstances and instead employs an <app> containing multiple <rdg> elements that denote different readings. Thus, for example, a correction in Codex Sinaiticus, quire 66, folio 5r, first column, line 5 is encoded as follows:

<app>

<rdg type=”main-corr”><w n=”11”>εδιδαξεν</w>

</rdg>

<rdg type=”corr” n=”ca”>

<w n=”11”>εδιδαϲκεν</w></rdg>

</app> (Codex Sinaiticus Project 2009)

The primary advantage of this method is how it permits editors to collate each reading separately. These readings, however, are editorial interpretations of the text and no clue is offered to the reader to judge how these interpretations were made. In other words, as Bordalejo notes, this method “makes no attempt to represent the document” (2010, 3).

§24 The Commedia Project leaders resolved this ambiguity of interpretation within the <app> (apparatus) element by modifying their use of the <rdg> (reading) element the former contains (Shaw 2010). The crucial innovation here is the “lit” (literal) “type” value of the <rdg> element. Within the <rdg type=”lit”> element, the transcriber encodes all the relevant text of the document in a manner that is as interpretation-free as possible while the interpretive act of understanding the distinct readings of that text is treated separately in “orig” (original) and “c1” values for the “type” attribute, where the number indicates which scribe is responsible for the correction (Bordalejo 2010, 6–8). This system has been only slightly adjusted for the CTP, which uses the “mod” (modified) value for the “type” attribute within the <rdg> element, since most of the time it is not possible to distinguish between multiple correcting hands.

§25 A particularly interesting example of an <app> element in the CTP is given in Figure 5 and is encoded as follows:

Scribal correction in Ne, folio 12v, line 844 of The General Prologue; Oxford, Bodleian Library New College.

<app>

<rdg type=”lit”>sort<seg rend=”int”>une</seg>

</rdg>

<rdg type=”orig”>sort</rdg>

<rdg type=”mod”>fortune</rdg>

</app>

In this example, the “lit” portion of the <app> element represents the text of the document regardless of which reading it is judged to belong to, while the “orig” (original) and “mod” (modified) readings contain the transcriber’s interpretation of the variant states of the text, namely, what the scribe originally wrote (“orig”) and what the transcriber understands the correction to signify (“mod”). One complicating factor in the example above is the initial letter which, although it undergoes no physical alteration, is nevertheless understood to change in meaning. The modified reading of the line in question renders as: “Were it by auenture, fortune, or caas” (Ne 12v, 844). The context of the line informs the interpretation of both readings. The Middle English word “sort” means “fortune” or “lot” and makes far more sense than “fort” in the original reading; it also corresponds logically with the scribal modification to “fortune” (“Sort, n. [1, 2].” 2019). Moreover, “sort” is also the archetypal reading in this line according to the CTP’s current collation of the passage:

sort ] Ad1 Ad2 Bo2 Bw Ch Cn Cp Dd Ds1 El En1 En3 Fi Gl Ha2 Ha3 Ha4 Hg Ht La Lc Ld1 Ld2 Ma Mg Mm Ne-orig Nl Ps Pw Py Ra2 Ra3 Ry1 Ry2 Se Sl1 Sl2 Tc1

scort ] Ln

shorte ] Ii

chaunce ] Bo1 Ph2

fortune ] Cx1 Cx2 Ne-mod Pn Tc1 Wy

The reading “fortune” is also a much more likely reading in general than the nonsensical “sortune”—if the final “une” were not an interlinear addition, most readers would doubtless not hesitate in understanding “fortune.” The judgment to understand “fortune” here is further corroborated by the scribe’s occasional inconsistency in crossing the letters “f” and long “s.” Indeed, on the very next line we see evidence of this in Figure 6, where the initial “s” of “soth” (transcribed as an “s”) has a more emphatic cross than many instances of the scribe’s “f.”

Crossed “s” in Ne, folio 12v, line 845 of the General Prologue; Oxford, Bodleian Library New College.

§26 Whether or not one agrees with these judgments concerning the readings “sort” and “fortune,” the example above highlights the advantage of using this form of the <app> tag. Rather than merely offering a set of interpretive judgments in isolation, the <app> tag instantiates the CTP team’s value of transparency: it provides readers with the information these judgments are based on as well as the means to evaluate those judgments—and to disagree should they see fit to do so. The <app> element signals a place of variation to the reader in the document and emphasizes that what has been transcribed is an interpretation (Bordalejo 2013).

§27 The CTP does not employ <app> tags in all cases of scribal alteration, however, but only for those which introduce a substantially variant reading or in cases where the transcription team wishes to highlight instances of variation. For example, an underdotted false start of a single letter is clearly not to be understood as an alternate reading of the following word. Therefore, it is simply encoded within a <hi rend=”ud”> tag. One example of this, found in the Lansdowne manuscript, is given in Figure 7, which is transcribed: Vpon hire <hi rend=”ud”>h</hi> chere—without an <app> tag. To use an <app> tag in such a case would be to treat the underdotted “h” as a variant reading of “chere” or as an altogether separate word which the scribe began to write, but never fully executed.

False start in La, 116r, line 238 of “The Clerk’s Tale.” MS 851 Landsdowne, London, British Library.

§28 Despite its strengths, the <app> tag is not perfect. One issue is that in the CTP’s current system nothing binds together all examples of specific types of scribal alteration. For example, though the project records the physical marks of underdotting, overwriting, erasure, and strikethrough with specific tags within the “lit” type of the <rdg> element, these activities are not explicitly categorized together as deletions within the transcription. As a result, there is no direct way to search for all instances of deletion; one would instead need to search separately for instances of underdotting, strikethrough, etc. This would not be the case if the project followed the TEI recommendation of using the <add> and <del> elements. However, addition and deletion, as Bordalejo suggests, “are not something that happen in a document, but are better described as the human interpretation of the text of the document, based on the reader’s understanding of the methods used by authors and transcribers to modify text” and not features of the document (Bordalejo 2010, 4–5). It is therefore fitting that they should remain at the level of interpretation for readers as well and not be features of the transcription. Each <app> element must be individually interpreted to understand the change it encodes.

§29 A second particularly significant change since the original transcription guidelines involves the CTP’s treatment of abbreviations. Many abbreviations in the original guidelines were not expanded at all (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 31–2). Instead, special characters were used to represent marks of abbreviation. This approach was adopted because the inconsistency of scribes posed too great a challenge to the system of encoding. In the original guidelines, Robinson and Solopova explain:

[…]the ambiguities and inconsistencies of scribal usage seen just in the comparatively brief section of The Wife of Bath’s Prologue transcribed forbade certain assignment of any one phonetic value to any one sign. Across the forty-eight manuscripts, it was found that in different manuscripts the one brevigraph could have different phonetic values and could even have more than one phonetic value in the same manuscript. (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 31)

This reasoning is sound, but it reflects a reliance on a particular feature of the TEI guidelines that the CTP no longer strictly adheres to. The statement that scribal inconsistency “forbade certain assignment of any one phonetic value to any one sign” is particularly telling. It points to the recommendation in the TEI guidelines to create a list of character definitions for each brevigraph (TEI P3, 6.4.5), but it is precisely this fundamental step that is impossible to achieve for such a multivarious and inconsistently used set of brevigraphs. If this task was unmanageable for transcribing only “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue”, how much more problematic would it be when tackling the entirety of the Tales? If the CTP was to include not only abbreviation marks but their expansions as well, it was clear that a more flexible approach was needed.

§30 The current system uses another set of TEI elements, namely a combination of the <am> (abbreviation mark) and <ex> (expansion) elements (TEI P5 2020, 11.3.1.2). Within the <am> element is transcribed the mark of abbreviation using a set of characters that resemble scribal usage (Baker 2018), while the <ex> element contains the transcriber’s interpretation of what that abbreviation signifies. Although only a limited set of symbols is available to the team’s transcribers (see the “Full Transcription Guidelines” for this list), the value of each is not predetermined. Of course, many abbreviation marks commonly signify a particular combination of letters, but the CTP’s system allows for unusual cases and, critically, for various possible expansions of a single mark. For instance, while “ł” might nearly always be expanded to the sequence “let,” abbreviation marks like the macron “ ̄ ” have multiple possible expansions depending on context, such as “n” or “m” when above a vowel, or in some circumstances nothing at all, as discussed further below.

§31 The examples below illustrate the current system of encoding abbreviations. The first example (Figure 8) is taken from “The Tale of Sir Thopas” and is transcribed as follows:

Abbreviation in Bw, folio 216v, line 97 of “The Tale of Sir Thopas”; Oxford, Bodleian Library.

<am>̱p</am><ex>per</ex>ilous

Here, the abbreviation mark “̱p” is expanded to “per” rendering the reading, “perilous.” Note, however, that in the expanded version, the stroke through the “p” is not reproduced so that in the edited view, it will appear in italics, i.e. “perilous.”

§32 Readers familiar with medieval manuscripts will be aware that the symbol “̱p” may stand for either “per” or “par” (Cappelli 1960). The current CTP transcription guidelines allow for the discretion of individual transcribers and editors to judge between possible expansions in such cases as these where it is not always possible to interpret the scribe’s intent. Occasionally, a word written with an abbreviation is also spelled out in full nearby in the same manuscript, in which case a transcriber can adopt that spelling for the expansion. In ideal circumstances, the transcription team might do the same in all cases regardless of where that full spelling may be. Scanning entire manuscripts for particular spellings in the page viewer during the initial transcription process, however, requires an enormous amount of time and effort that becomes difficult to justify. Moreover, it often happens that all instances of a particular word in a manuscript are abbreviated or the scribe uses various spellings—in either case it remains impossible to reliably reconstruct the scribe’s intended spelling. Accordingly, in cases of abbreviation where multiple expansions may be equally justified, the transcription team expedites this process by expanding the abbreviation with their best guess based on the context. Moreover, in such cases the collation phase of the project involves regularizing to whatever spelling is most commonly found in the Hengwrt manuscript (Hg), one of the earliest manuscript witnesses. This decision simplifies and streamlines the transcription process for the CTP team, while a transcriber’s interpretation in such cases may later be regularized by the project leaders.

§33 A second example (Figure 9) comes from the same manuscript and is transcribed as follows:

Abbreviation in Bw, folio 58v, line 342 of “The Reeve’s Tale”; Oxford, Bodleian Library.

þ<am>u</am><ex>ou</ex>

Here, the superscript “u” abbreviates “ou” since “þou” is the usual form in the Middle English corpus of this form of the second person singular pronoun in the subject case (“thǒu, pron.” 2019). It is nevertheless possible that the scribe did not intend the superscript “u” as an abbreviation, but rather as a customary way of writing this particular word—superscript letters and other marks that may commonly be used for abbreviation do not always signify abbreviation. The spelling “þu” does very occasionally occur in some manuscripts of the Tales, but these are outliers and the CTP team chooses to treat the superscript “u” as an abbreviation for the sake of consistency.

§34 Besides these major shifts in transcription practice there are several smaller changes that the CTP team has made since the original guidelines were formulated that bear mentioning. Some of these are simple character replacements made possible by Peter S. Baker’s development of Junicode, a font designed specifically for medievalists which includes a large array of special characters (Baker 2018). For instance, the guidelines now contain an updated list of abbreviation marks, including: “ʆ” for “sir” or “ser” and  for final “-es” or “-is.” There are also now abbreviation marks available that combine with the preceding character, such as the combining macron “̄” and the “er” or “re” abbreviation,“ ̄ ”, which enable greater flexibility when encountering unusual uses of these symbols. There were also cases where Junicode allowed for the replacement of certain “entities” from Collate2 such as “é” into a single Junicode character, “é” (Robinson 1991). The development of Junicode has also allowed for certain changes to the CTP transcription team’s use of punctuation marks. Accordingly, the CTP transcription guidelines now contain both the mid dot “·” and the punctus elevatus

for final “-es” or “-is.” There are also now abbreviation marks available that combine with the preceding character, such as the combining macron “̄” and the “er” or “re” abbreviation,“ ̄ ”, which enable greater flexibility when encountering unusual uses of these symbols. There were also cases where Junicode allowed for the replacement of certain “entities” from Collate2 such as “é” into a single Junicode character, “é” (Robinson 1991). The development of Junicode has also allowed for certain changes to the CTP transcription team’s use of punctuation marks. Accordingly, the CTP transcription guidelines now contain both the mid dot “·” and the punctus elevatus  , as well as the rarer trifinium “∴” and wedge “▽”. Transcribers on the project also now use a simple slash “/” to represent virgules, though when these are attached to the preceding word they treat them as ornamental flourishes and do not record them. Transcribers no longer record an initial double “f” as “ff,” but understand it as how most scribes formed the capital letter and so transcribe it as a capital “F” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 42). Similarly, the crossing of double “l” (ƚƚ) is regarded simply as customary or ornamental and only recorded and interpreted as an abbreviation of final “e” when its rhyming pair likewise ends with an “e”. An example of this occurs in The Franklin’s Tale (see Figure 10), which is encoded as “sha<am>ƚƚ</am><ex>lle</ex>” in order to correspond with the spelling “alle” in the preceding line with which it rhymes. The CTP team has also added a number of abbreviation marks to the guidelines which tend to occur only in Latin words, such as:

, as well as the rarer trifinium “∴” and wedge “▽”. Transcribers on the project also now use a simple slash “/” to represent virgules, though when these are attached to the preceding word they treat them as ornamental flourishes and do not record them. Transcribers no longer record an initial double “f” as “ff,” but understand it as how most scribes formed the capital letter and so transcribe it as a capital “F” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 42). Similarly, the crossing of double “l” (ƚƚ) is regarded simply as customary or ornamental and only recorded and interpreted as an abbreviation of final “e” when its rhyming pair likewise ends with an “e”. An example of this occurs in The Franklin’s Tale (see Figure 10), which is encoded as “sha<am>ƚƚ</am><ex>lle</ex>” in order to correspond with the spelling “alle” in the preceding line with which it rhymes. The CTP team has also added a number of abbreviation marks to the guidelines which tend to occur only in Latin words, such as:  for “rum”;

for “rum”;  for final “ue” or sometimes “us”; and “oıı̄ıı̄” for “omnium.” Finally, note that transcribers on the project also interpret the Tironian et,

for final “ue” or sometimes “us”; and “oıı̄ıı̄” for “omnium.” Finally, note that transcribers on the project also interpret the Tironian et,  as abbreviating “et” in Latin contexts, such as in the commonplace

as abbreviating “et” in Latin contexts, such as in the commonplace  for “et cetera.” The rest of the time (i.e. in a Middle English context) transcribers expand the same symbol to “and.”

for “et cetera.” The rest of the time (i.e. in a Middle English context) transcribers expand the same symbol to “and.”

Final “e” abbreviation in Ld2, folio 178r, lines 41–2 of “The Franklin’s Tale”; Oxford, Bodleian Library.

Resource optimization

§35 While some questions of abbreviation deal with issues of consistency, there have been other instances where adhering to the CTP’s original guidelines would require a tremendous amount of time and effort for the project with little payoff. Instead, the guidelines serve to maintain a balance of clarity and economy of effort while prioritizing the project’s ultimate aims of a collatable, accessible, digital transcription.

§36 In the original transcription guidelines, Robinson and Solopova distinguished between a macron and a flourish as different strokes by a scribe, but had a tendency to record both even in cases where the macron or flourish might signify nothing such as in “man̄, certeyn̄ or in spellings like doun̄” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 37). Their discussion of macron “n” resulted in the following decisions:

-

where there is no mark of abbreviation, we interpret the minims as n;

-

where there is a mark of abbreviation, we interpret the minims as u, with the mark representing abbreviation of the final n. (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 38)

Both acknowledge that this is not a perfect solution and many problems and inconsistencies arise but they “feel that following this rule leaves less scope for interpretation and decision-making by every transcriber in each individual case” (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 38). The CTP’s guidelines on this issue continued to develop with this principle in mind, attempting to streamline the decision-making process for the transcriber for both economy of effort and consistency.

§37 Later, in the project’s “Full Transcription Guidelines,” Bordalejo and Robinson (2018) identify the category of “Marks which might or might not be abbreviations.” In general, the guidelines for such marks advised that transcribers “record the mark, but do not give an expansion” (Bordalejo and Robinson). That is, transcribers record both the letter and the scribal sign which may be interpreted as an abbreviation in the manuscript but do not expand it with an interpretation (i.e. transcribers do not implement the <am> and <ex> tags in these cases). They acknowledge there are cases where a macron may be ambiguous because it appears over a final “n” that could potentially be a “u”. In these cases, they propose merely recording it with “n̄”. However, they conclude the section with somewhat of a catchall: “If it appears the stroke is simply ornamental, ignore” (Bordalejo and Robinson 2018). These practices depended greatly on transcriber interpretation and could lead to a great degree of inconsistency. So, Robinson and Bordalejo developed a system based on the observation of minim strokes expressed in the “Quick Start Transcription Guide” (Robinson 2018).

§38 Here, the guidelines depend not upon a transcriber’s judgment of whether strokes are ornamental, but a simple decision about whether or not one deems an abbreviation possible. Where abbreviation is not possible, the macron signifying nothing, a transcriber now simply records “n̄”. Where one does interpret abbreviation as possible, a transcriber records a different abbreviation based on what letter the minims appear to be. The “Quick Start Guide” breaks down macrons over minim pairs into multiple possible scenarios for n̄:

No abbreviation n̄ (in̄ upon̄ doun̄ gypoun̄ -- prepositions adverbs nouns in -oun̄)

Where abbreviation u+n is possible (condicion̄; nouns in on̄):

appears u: <am rend=”ū”>ıı̄</am><ex>un</ex>

appears n: <am rend=”n̄”>ıı̄</am><ex>un</ex>

appears neither n nor u: <am>ıı̄</am><ex>un</ex> (“Quick Start Guide” Robinson)

These distinctions allow the CTP’s transcribers to record certain nuances of scribal abbreviation. Rather than obfuscate what is actually present in the text by supplying their own interpretation or excising significant marks entirely, transcribers allow readers to judge between possible interpretations of the macron and minims for themselves. Moreover, transcribers save time because they are not expected to distinguish between essentially indistinguishable letters (i.e. the minim pair). They can defer judgment to the reader by simply recording the minim pair and macron rather than deciding between their possible interpretations.

§39 Another instance where the CTP team has changed its transcription practice in favour of an economy of effort is how the project negotiates the use of the hook abbreviation ( ͗ ) denoting a final “e”. Originally, the transcription guidelines were primarily concerned with a single circumstance of this abbreviation, the flourish or hook that occurs after a final “r”. Because it appeared indistinguishable from such a flourish occurring over a final “u”, which usually abbreviated an “n”, the team encoded both instances of the flourish as a macron over their respective letters: ū, r̄ (Robinson and Solopova 1993). However, the complexities of representation of a macron over two minims (see 36–38) and the stark realization that one could not always guarantee that a flourish at the end of a word abbreviated anything, let alone a particular letter, prompted a change in transcription practice. As a result, the CTP’s transcribers now record these symbols as distinct markings: they record flourishes over a final “r” when reasonably confident of an abbreviation with the hook mentioned above ( ͗ ), and expand it to “e” and treat flourishes over a “u” as macrons. While the appearance of the stroke itself may be identical, transcribers take into account the position of the flourish to judge whether they ought to record it as a hook or macron. In other words, although these strokes may appear identical in a manuscript, they are recorded with different signs based on their graphemic context.

§40 The original transcription guidelines paid particular attention to flourishes at the end of words but advised one not to record a flourish if it was merely decorative, which is still the current practice. It also became apparent that it would be difficult to establish consistent practices across manuscripts as even the use of a flourish after a single word such as “well” could require extensive discussion (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 35). By and large, the original CTP guideline more freely attributed meaning to a final flourish than its current counterpart.

§41 In the project’s current practice, the guidelines emphasize that one should transcribe a flourish at the end of a word as an abbreviation only when one can be reasonably certain it is intentional and meaningful. For instance, there is doubt that a final “e” should always be recorded simply because a flourish is present at the end of the last word of a line which might resolve the metre. Nor should the final “e” be added simply to regularize a spelling or make it match modern convention. As a result, the transcription of such an abbreviation is rarer. Where one does encounter the abbreviation of final “e”, the current practice for CTP transcribers is to record it as follows:

final r with abbreviation: normally -e, i ei: eg hir͗ for hire: hir<am>͗</am><ex>e</ex> (Bordalejo and Robinson 2018)

This change in convention is the result of both a change in the treatment of macron “u” as well as the availability of more specific and accurate symbols through the advent of Junicode. Emphasizing the need for certainty when choosing to interpret the flourish at the end of a word as an abbreviation for final “e” reduces the amount of time a transcriber spends agonizing over minutiae that they may not be sufficiently informed to discern in the first place.

§42 Another case is the project’s shift in practice concerning the capitalization of initial letters in each line of verse. At first, the project leaders took great pains to determine a convention for each manuscript on a case by case basis:

Some scribes (e.g. Hg) clearly intend to use the emphatic form always at line beginnings, but this intention is obscured by the lack of distinct upper-case forms. In the face of this uncertainty, consistency and accuracy are very difficult to achieve. We discriminate in our transcription between emphatic forms at line beginnings and within the line. Where the scribe’s practice shows that he uses separate upper-case forms at the line beginnings for all letters which have such distinct forms, then we elect to transcribe as emphatic all first letters of lines, including those letters for which the scribe has no distinct emphatic form. (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 42)

Even in 1993, Robinson and Solopova had already developed descriptions of capitalization for some half a dozen manuscripts that included specific best practices for transcription in each and this is the same practice still executed by the editors of the PPEA, who insist that in their own project, “[p]olicy decisions with regard to capitalization can be made only after analysis of each individual manuscript” (“Transcriptional Protocols”). Beyond a decision on how to represent the first letter of each line, descriptions in the CTP’s original guidelines went so far as to include the specific variations in emphatic and unemphatic forms of individual letters (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 42–3). While this valuable work can help answer important questions as in Ha4, where “the closeness of the practice of Cp and Ha4 supports the argument that the two manuscripts are written by the one scribe,” carrying out such detailed work for the entire corpus of witnesses is a monumental task (42).

§43 Developing such descriptions and guidelines for each manuscript takes valuable time and resources, especially in light of how little such a distinction matters during the process of collation itself. As a result, the current project guidelines regarding capitalization in verse have been streamlined:

We transcribe capitals when the letter form in the manuscript is emphatic, that is, different from the regular lower case letter. However, we always transcribe a capital at the beginning of the line, whether the letter is upper or lower case. (“Capitalization,” Bordalejo and Robinson 2018)

While this might seem an extreme change, it clearly benefits the economy of effort on the project. First, there is little to no practical change to the outcome of collation, a primary end of the CTP’s transcription. Second, not only do project leaders not have to expend time and energy on these guidelines, transcribers (whether paid or volunteer) no longer need to learn the practices for each manuscript. The confusion of manuscript-specific guidelines almost certainly costs the project in errors as well as time.

§44 The more straightforward and consistent a project can make its transcription practices, the better chance its transcribers will make fewer errors and its leaders will spend less time clarifying those rules to transcribers. Incorporating an economy of effort into the CTP’s transcription guidelines, though it may sometimes result in the loss of a particular level of specificity, better serves the project as a whole without compromising the transcription and collation processes. Difficult as it may be, project leaders are bound to determine what is practically best for their projects in terms of time and resources. In the case of the CTP, this entails aiming for a sound transcription that sets the stage for many potentially interesting projects and making its transcription freely accessible for others to pick up the project’s work and adapt it for research of a greater specificity.

Improvisation and the need for flexibility

§45 While the CTP guidelines are designed to provide clear instructions for the treatment of uncommon circumstances in transcription as best they can, there are certain cases where one must depend on the transcriber’s ability to discern and interpret the manuscript without relying upon rigid guidelines. Sometimes, this is because one cannot anticipate every permutation of an abbreviation or the inconsistent ways in which particular scribes adapt conventions of abbreviation. For instance, there are relatively standard expansions for macrons such as an “m” or “n”. However, a scribe might use a macron to abbreviate many different letters and often context is the best way to interpret the appropriate transcription. The same is true with how scribes record sacred names. It is often quite clear that the intended name is “Jesus” or “Jerusalem” but the abbreviated forms scribes might use vary.

§46 Rather than develop rigid and byzantine guidelines on every question of interpretation specific to each manuscript, the CTP instead relies upon the transcriber to interpret the manuscript based upon their own experience with that manuscript and others, the context of the particular passage they are transcribing, and their knowledge of the guidelines that are in place. If a transcriber still cannot make a decision in a given case, he or she can raise the problem with the project leaders, who will make a judgment based on the CTP’s transcription principles and aims. The structure of the CTP’s transcription team also ensures that senior transcribers and project leaders review these unique cases, and indeed all transcriptions. The following examples demonstrate certain instances where relying upon improvisation is preferable to a more exhaustive guideline structure.

§47 Perhaps one of the best instances of this need for flexibility and improvisation is the abbreviation of sacred names. The ubiquity of nomina sacra such as “Jesus,” “Christ,” or “Jerusalem,” and perhaps the fact that they are distinct from common medieval English names, results in various configurations of their abbreviation in witnesses containing the Canterbury Tales. For example, the name of Jesus, often rendered as “Ihesu” by medieval scribes, can have a number of spellings and abbreviations. Originally, the CTP’s guidelines recorded the many instances found because of Robinson and Solopova’s interest in the use of the macron in abbreviated forms of “Ihesu”. Thus, abbreviations such as “Iħus”, “Iħu “, “iħu”, and “iħc” are explicitly mentioned in the original guidelines (Robinson and Solopova 1993, 32). Abbreviations can even feature Greek letters, as in “xħu” for Ihesu or “xp̄” as an abbreviation for Christ. The CTP’s current full transcription guidelines record instances such as these in a section of “more complex abbreviations” (Bordalejo and Robinson 2018). The guidelines also record some of the most common forms of sacred names in its “Quick Start Guide.” This includes “Iħu,” “Ierlm̄,” “xp̄o,” “eccliāste,” and “dd” as abbreviations for “Ihesu,” “Ierusalem,” “Christo,” “ecclesiaste,” and “Dauid”. However, unlike The Cotton Nero A.x. Project that documents every instance of a unique abbreviation of a nominum sacrum—for instance, they encode seven distinct abbreviated forms of “Jerusalem”—that appears in the manuscript (Olsen and McGillivray 2011), the CTP team has opted to provide only the most common instances and trust that its transcribers can interpret distinct abbreviated forms without a comprehensive list of examples in its guidelines to rely upon.

§48 The CTP guidelines aim to give the transcriber a large enough sample of the abbreviations so that they might recognize any new formulations a scribe presents and understand how to correctly encode them. The guidelines do not record every iteration or permutation of even the most common nomina sacra. Instead, they rely upon the transcriber to discern the best way to encode these commonly abbreviated words when the scribe has recorded them in an unorthodox manner.

Conclusion

§49 The many changes in the CTP’s transcription practices detailed above are both a reinvestment in its foundational principles and a perspective on the continuing development the project has experienced over the last twenty-eight years. But it is important to acknowledge that even the work of a project as long-standing as the CTP is only a stepping stone to further scholarship. In fact, Robinson has reinforced this fundamental principle of the guidelines again and again. In his article, “What Text Really is Not,” he frames the goals of the project as a means to give readers access to new texts that they can make themselves:

Our aim over the next decades is to transform the way people read the Canterbury Tales. We want readers to understand just what it is they are reading, so that they can make texts for themselves with new intelligence. If they do this, then our text will be outdated: and frankly, it will not matter then if people can no longer read our text, and I will not care if they cannot. The great promise of electronic editions, to me, is not that we will find new ways of storing vast amounts of information. It is that we will find new ways of presenting this to readers, so that they may be better readers. (Robinson 1997, 50)

Robinson acknowledges the ephemerality of the text and freely gives it up as something that will quickly become outdated once others have access to the CTP’s transcriptions. Yet even these transcriptions are not safe, as Robinson predicts an interest in greater levels of specificity and the obsolescence even of the monumental task and resource of the CTP’s transcription:

In 100 years time, scholars will be interested in these different letter forms, and will want transcriptions which record them. Our transcripts will be outdated and of no interest to anyone except the occasional digger into archives. (Robinson 1997, 50)

And yet, the contribution of the project remains clear: the transcription is a means to more informed texts, better quality editions, and, eventually, still more detailed transcriptions. It has been and continues to be a task that requires tremendous collaboration and effort in service to a wider community of Chaucer scholars and editors. Paradoxically, the CTP’s task is to be overcome: the ideal end of the entire project is its own obsolescence in the wake of future projects made by those who have become better readers.

Acknowledgements

We owe a great debt to the CTP’s leaders, Barbara Bordalejo and Peter Robinson for their feedback and advice during the conceptualization and writing of this paper. And, of course, this paper would have been impossible without the work of our transcription team and all current and former collaborators. We would further like to acknowledge the funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada that made our paid involvement in the project possible.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Contributions

Editorial

Recommending editors:

Barbara Bordalejo, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Franz Fischer, Ca’ Foscari Università Venezia, Italy

Recommending referees:

Paolo Monella, University of Palermo, Italy

Murray McGillivray, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Section/Copy/Layout editor:

Shahina Parvin, Journal Incubator, University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada

Authorial

Authorship is alphabetical after the drafting author and principal technical lead. Author contributions, described using the CASRAI CredIT typology, are as follows:

Kendall Bitner: KB

Kyle Dase: KD

Authors are listed in alphabetical order as equal contributions were made in all roles. The corresponding author is Kyle Dase

Conceptualization: KB, KD

Writing – Original Draft Preparation: KB, KD

Writing – Review & Editing: KB, KD

References

Baker, Peter S. 2018. “Junicode.” Junicode. June 25, 2018. https://junicode.sourceforge.io/.

Barbrook, Adrian C., Christopher J. Howe, Norman Blake, and Peter Robinson. 1998. “The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales.” Nature 394(6696): 839. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1038/29667

Bordalejo, Barbara. 2010. “VII. Appendices: C: The Commedia Project Encoding System.” In Commedia, edited by Prue Shaw. Birmingham: Scholarly Digital Editions. Accessed September 9, 2020. http://sd-editions.com/AnaAdditional/commediaonline/home.html.

Bordalejo, Barbara. 2013. “The Texts We See and the Works We Imagine: The Shift of Focus of Textual Scholarship in the Digital Age (Published Version).” Ecdótica 10: 64–76.

Bordalejo, Barbara, and Peter Robinson. 2018. “Full Transcription Guidelines.” Wiki. Canterbury Tales Project 2. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://wiki.usask.ca/display/CTP2/Full+transcription+guidelines.

Cappelli, Adriano. 1960. Dizionario di Abbreviature Latine ed Italiane. 6th ed. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli.

Codex Sinaiticus Project. 2009. Accessed March 5, 2021. http://www.codexsinaiticus.org/en/.

Cotton Nero A.x. Project. 2010. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/projectnew.html.

Olsen, Kenna L., and Murray McGillivray. 2011. “Cotton Nero A.x. Project Transcription Policy.” The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Publications of the Cotton Nero A.x. Project 2. Calgary: Cotton Nero A.x. Project. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/cotton/policy.html.

Parker, David C. 2008. An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511619922

Parkes, Malcolm B. 1992. Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Aldershot, Hampshire: Scolar Press.

Pierazzo, Elena. 2011. “A Rationale of Digital Documentary Editions.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 26(4): 463–77. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr033

PPEA (Piers Plowman Electronic Archive). 2019. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://piers.chass.ncsu.edu/.

Robinson, Peter. 1991. Collate (version Release 1.0). Oxford: Computers and Manuscripts Project. Leicester: Centre for Technology and the Arts.

Robinson, Peter. 1997. “What Text Really Is Not, and Why Editors Have to Learn to Swim.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 24(1): 41–52. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqn030

Robinson, Peter. 2018. “Quick Start Transcription Guide (for Canterbury Tales Project and Other Medieval Texts).” Wiki. Textual Communities. Accessed October 2, 2020. https://wiki.usask.ca/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=1279393884.

Robinson, Peter. 2021. “Creating and Implementing an Ontology of Texts, Documents and Works in Complex Textual Traditions.” DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4006582

Robinson, Peter, and Elizabeth Solopova. 1993. “Guidelines for Transcription of The Manuscripts of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue.” In The Canterbury Tales Project Occasional Papers, edited by Norman Francis Blake and Peter Max Wilton Robinson, I: 19–52. Oxford: Office for Humanities Communications.

Shaw, Prue, ed. 2010. Commedia. By Dante. Birmingham: Scholarly Digital Editions. Accessed December 20, 2020. http://sd-editions.com/AnaAdditional/commediaonline/home.html.

“Sort, n. (1, 2)” 2019. Middle English Dictionary (MED). Online Edition in Middle English Compendium. Edited by Frances McSparran, et al. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/.

“Thǒu, pron.” 2019. Middle English Dictionary (MED). Online Edition in Middle English Compendium. Edited by Frances McSparran, et al. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/.

TEI P3. 1999. Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Edited by Sperberg-Mcqueen, C. M. and Lou Burnard. Chicago, Oxford: Text Encoding Initiative. 1999. Accessed March 17, 2021. https://tei-c.org/Vault/GL/P3/index.htm.

TEI P5. 2020. Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. Edited by TEI Consortium. Accessed March 17, 2021. http://www.tei-c.org/Guidelines/P5/.

Manuscripts

Ad3. London, British Library, Additional MS 35286.

Bo2. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodl. 686 [s.c. 2527].

Bw. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Barlow 20 [s.c. 6420].

Cn. Austin, University of Texas, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center HRC Pre-1700 MS 143.

Hg. Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, Peniarth, 392 D.

La. London, British Library, Lansdowne MS 851.

Ld2. Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Laud Misc. 739 [SC. 1234].

Ne. Oxford, Bodleian Library New College, Oxford MS 314.